Collective Consciousness, Individuality, and Transgenerational Conditioning: A Multidisciplinary Perspective

Abstract

This article examines the intersection of collective consciousness, educational systems, individuality, and transgenerational conditioning, with a particular focus on early exposure to addictive behaviors. Drawing on findings from sociology, psychology, neuroscience, and epigenetics, it explores how societal frameworks influence selfhood, how trauma and substance use may be inherited across generations, and how compassion and self-reflection contribute to resilience.

1. Introduction

Human consciousness emerges not only from individual neural processes but also from deeply social contexts. Social environments such as schools, religious institutions, and political systems provide a framework for shared beliefs and behaviors. While such systems are designed to ensure cohesion and order, they often diminish individuality and suppress personal exploration. At the same time, inherited vulnerabilities—biological, cultural, and psychological—shape predispositions toward certain behaviors, including substance use. Understanding these dynamics requires a holistic approach that integrates sociological, psychological, and biological perspectives.

2. Collective Consciousness and Group Dynamics

The concept of collective consciousness describes the shared values, beliefs, and norms that bind individuals together within a group. In early educational settings, this manifests as children adopting collective behaviors—moving together, speaking together, and aligning with peer norms. While such conformity fosters belonging, it can also suppress the development of individuality.

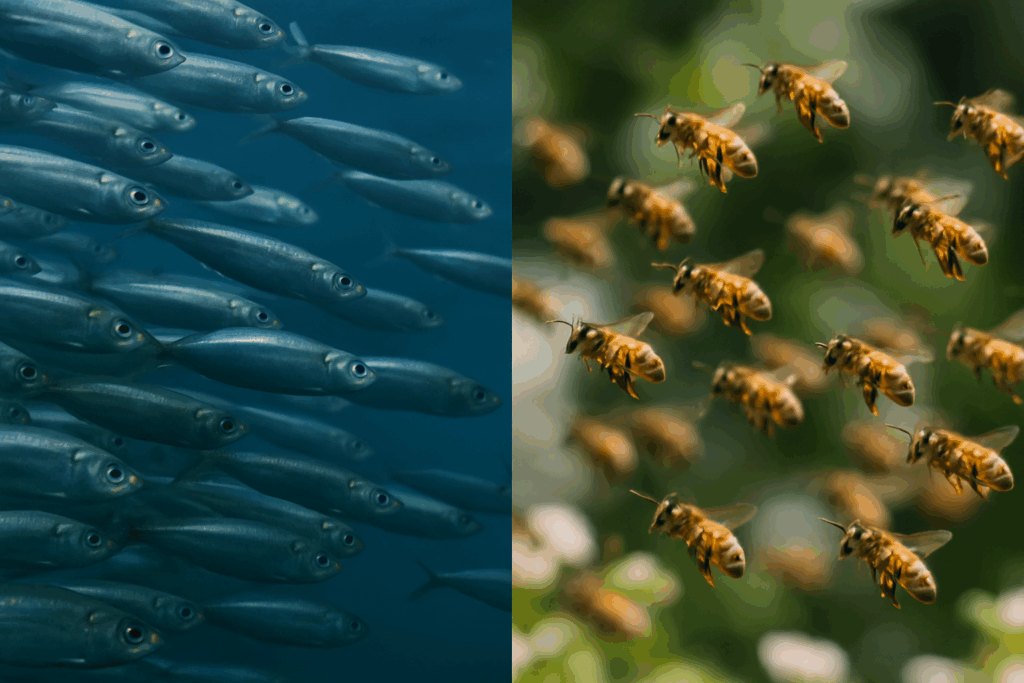

Group dynamics in childhood often resemble natural metaphors: schools of fish moving in synchrony or swarms of bees buzzing in chaotic unison. Both analogies capture the tension between safety in numbers and the risk of losing autonomy. Psychological studies show that collective influence can override individual judgment, leading children and adults alike to conform to group decisions, even when those decisions contradict personal perceptions.

3. Educational Systems and Individual Autonomy

Educational institutions often serve as the first large-scale social system encountered by children. While schools aim to cultivate intellectual and moral growth, they also enforce conformity through standardized curricula, rules, and authority structures. This balance between guidance and suppression is delicate.

Philosophers of education have long argued that true learning requires the nurturing of individuality. Yet, in practice, many children experience education as a form of systemic control, where questioning authority or exploring unconventional ideas is discouraged. The result can be alienation, where students feel reduced to interchangeable parts within a larger machine.

4. Substance Use as a Developmental “Bridge”

A critical dimension of individuality arises when children and adolescents experiment with behaviors that provide escape or altered states of consciousness. Early experimentation with alcohol, for example, often serves as a “bridge” away from difficult realities. For some, alcohol provides warmth, relaxation, or temporary relief from anxiety. However, the risks of early initiation are profound.

Neuroscientific research shows that the developing brain is particularly vulnerable to alcohol’s effects. Early exposure increases the risk of long-term dependence, cognitive impairments, and heightened impulsivity. Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated that individuals who begin drinking before the age of 15 are significantly more likely to develop alcohol use disorders later in life compared to those who delay initiation.

5. Transgenerational Trauma and Epigenetic Inheritance

One of the most striking insights of modern science is that patterns of behavior and vulnerability are not only learned socially but can also be transmitted biologically. The study of epigenetics demonstrates how environmental experiences—such as trauma or substance exposure—can leave molecular “marks” on DNA that influence gene expression across generations.

Research in animal models has shown that parental alcohol consumption can affect offspring through changes in DNA methylation and other epigenetic mechanisms. In humans, intergenerational studies reveal that children of individuals exposed to severe trauma (e.g., war, famine, or systemic oppression) often show altered stress responses, increased anxiety, and greater susceptibility to psychiatric disorders. This suggests that both substance use and trauma may echo across generations, encoded not only in culture but also in biology.

6. The Role of Social and Economic Contexts

Beyond biology, cultural and economic factors strongly shape patterns of addiction. Historical legacies of poverty, social injustice, and systemic oppression create environments where substance use may become a widespread coping mechanism. Alcohol, in particular, has played a prominent role in societies marked by conflict, scarcity, or harsh climates, often becoming a socially acceptable way to manage stress and hardship.

In contemporary contexts, unemployment, inequality, and social alienation continue to contribute to widespread alcohol consumption. These patterns reveal how individual choices are rarely isolated acts of willpower, but rather emerge at the intersection of personal predisposition, cultural inheritance, and socio-economic conditions.

7. Self-Reflection, Compassion, and Healing

While transgenerational conditioning and systemic pressures are powerful, they do not determine outcomes absolutely. Psychological resilience emerges when individuals engage in self-reflection, confront inherited patterns, and cultivate compassion—both for themselves and for those who came before them.

Narrative practices, such as writing, therapy, or storytelling, often serve as powerful tools of healing. By reinterpreting one’s past and acknowledging intergenerational influences without judgment, individuals can transform cycles of trauma into opportunities for growth. Self-compassion, in particular, has been linked to lower levels of stress, greater psychological well-being, and healthier coping strategies.

8. Conclusion

Human development is shaped by the interplay of collective consciousness, systemic structures, inherited vulnerabilities, and personal choices. Educational institutions and societal systems play a dual role, offering both support and suppression. Transgenerational trauma and epigenetic inheritance highlight how the past continues to shape the present, often in unseen ways. Yet within this complex web lies the possibility of transformation. Through self-awareness and compassion, individuals can disrupt cycles of trauma and addiction, building new “bridges” that connect mind, body, and soul in healthier, more authentic ways.

References

- Durkheim, É. Collective consciousness as the moral glue of society Wikipedia.

- Halbwachs, M. Collective memory as a social construct Wikipedia.

- Shteynberg, G. Psychological contours of collective consciousness and its effects myscp.onlinelibrary.wiley.com.

- General theory of collective mind and individual cognition Chicago Journals.

- Dewey, J. My Pedagogic Creed on education and individual–society relationship Wikipedia.

- Multigenerational transmission of substance effects (animal models) PubMed CentralScienceDirect.

- Epigenetic markers in offspring of Holocaust survivors (Nr3c1 methylation) Wikipedia.

- Intergenerational trauma and brain research, mitochondrial and metabotranscriptome changes Nature.

- Historical Intergenerational Trauma Transmission (HITT) model ResearchGate.

- Overview of intergenerational trauma and its health impacts