Intergenerational Perspectives on Aging, Mortality, and Longevity: A Scientific and Philosophical Synthesis

Abstract

Aging and mortality are universal human experiences shaped by biology, psychology, and cultural context. While genetic predispositions play a central role in longevity, lifestyle choices, psychosocial factors, and spiritual frameworks also influence health trajectories. This article explores contemporary scientific understandings of aging, intergenerational relationships, and the possibility of extending healthspan. Drawing on genetics, epigenetics, psychology of aging, and contemplative practices, the discussion emphasizes both the limits and potentials of human longevity.

1. Introduction

The inevitability of aging and death has long been a central concern of philosophy, religion, and science. While biology sets boundaries on human lifespan, cultural narratives and individual choices influence how aging is experienced. Advances in genetics, neuroscience, and psychosomatic research reveal that aging is not only a product of molecular decline but also of psychosocial and behavioral factors (López-Otín et al., 2013).

2. Genetics and Inherited Vulnerabilities

Longevity is partly determined by heritable genetic factors. Twin studies suggest that genetic variation accounts for approximately 20–30% of lifespan differences, with the remainder influenced by environment and lifestyle (Herskind et al., 1996). Specific genes, such as those related to insulin/IGF-1 signaling and DNA repair, are linked to increased lifespan in both model organisms and humans (Kenyon, 2010).

Moreover, genetic predispositions to disease — such as BRCA mutations for cancer or APOE4 alleles for Alzheimer’s — highlight the role of inherited risk. However, these risks are not deterministic; epigenetic modifications and lifestyle interventions can alter gene expression, shaping health outcomes across the lifespan (Horvath & Raj, 2018).

3. The Role of Lifestyle and Behavioral Choices

While genetics set the foundation, choices around diet, exercise, and substance use profoundly impact aging trajectories. For instance:

- Smoking remains one of the strongest behavioral predictors of premature death, reducing life expectancy by up to 10 years (Doll et al., 2004).

- Diets rich in plant-based foods are associated with reduced all-cause mortality and lower incidence of chronic disease (Orlich et al., 2013).

- Excessive alcohol and drug use contribute significantly to global morbidity and mortality (Rehm et al., 2009).

The concept of cause and effect, central in both science and philosophy, is evident in epidemiology: early-life behaviors predict long-term outcomes. In this sense, lifestyle is a bridge between free will and biological determinism.

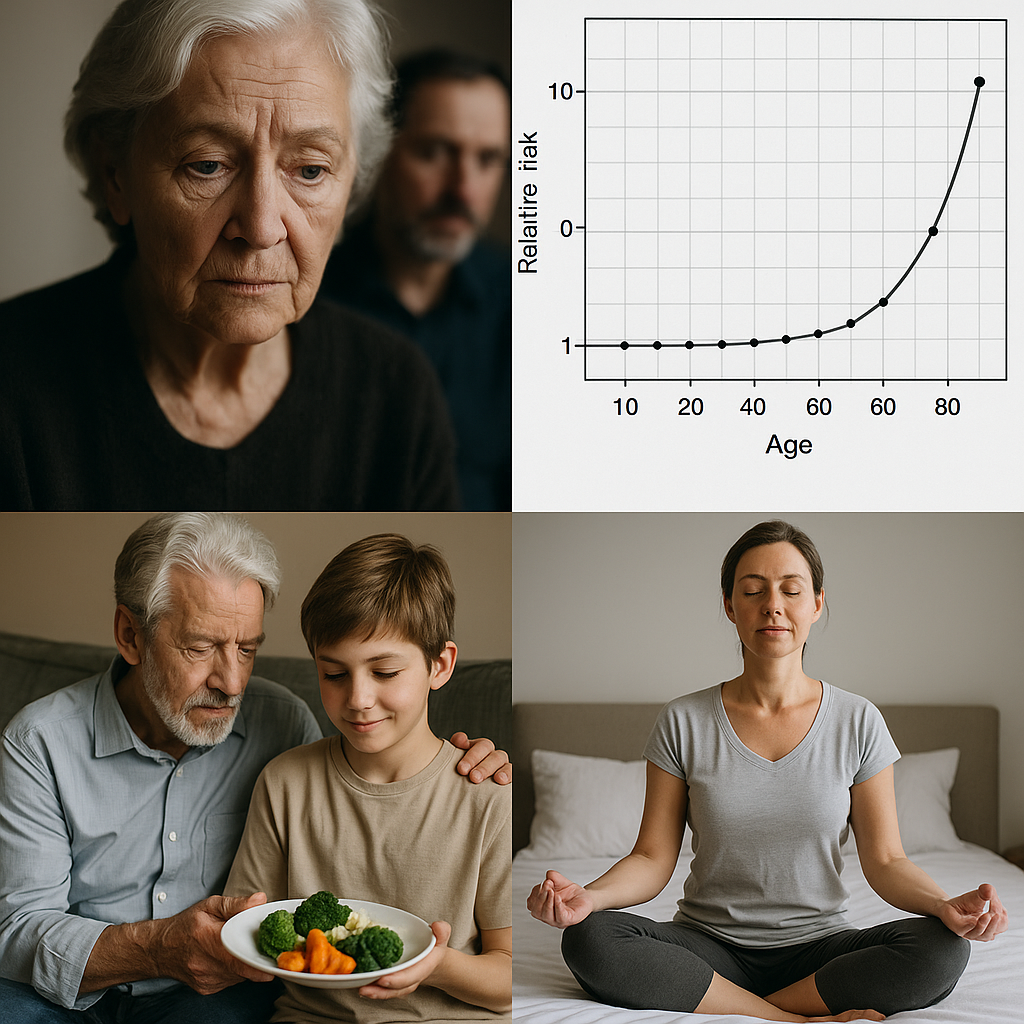

4. Psychological Dimensions of Aging

Aging is not merely biological but also psychological. Fear of parental mortality, common in childhood and adulthood, reflects the centrality of intergenerational bonds in shaping identity (Kübler-Ross, 1969). The psychological response to mortality awareness can foster existential anxiety but also motivate meaning-making behaviors (Becker, 1973; Pyszczynski et al., 2015).

Moreover, cognitive-emotional health plays a vital role in longevity. Studies show that positive affect, purpose in life, and social connectedness are associated with reduced mortality risk (Steptoe & Fancourt, 2019). Conversely, rumination on loss and isolation accelerate decline.

5. Spirituality, Consciousness, and Longevity Practices

Beyond genetics and behavior, many traditions emphasize the unity of body, mind, and spirit as essential for health. While immortality remains beyond scientific validation, certain contemplative practices have measurable effects:

- Meditation and mindfulness reduce stress biomarkers, improve immune function, and may influence epigenetic aging clocks (Epel et al., 2016; Chaix et al., 2017).

- Breathwork, fasting, and visualization are shown to impact autonomic regulation and metabolic processes (Longo & Mattson, 2014).

- Spiritual frameworks of meaning are correlated with resilience and healthier aging outcomes (Koenig, 2012).

These findings suggest that spiritual practices may serve as mediators between psychological states and physiological outcomes, reinforcing the importance of a holistic approach to longevity.

6. The Intergenerational Dimension

Parents often serve as emotional “umbrellas,” shaping early perceptions of mortality, health, and responsibility. Intergenerational dialogues about lifestyle and mortality reflect broader cultural tensions between tradition and innovation. Research shows that parental modeling strongly influences children’s health behaviors, from diet to substance use (Patrick & Nicklas, 2005).

Thus, familial relationships become not only sites of emotional attachment but also vectors of health transmission across generations. The challenge lies in balancing respect for autonomy with the promotion of healthier practices.

7. Conclusion

Aging is shaped by a dynamic interplay of genetics, lifestyle, psychological states, and cultural meaning systems. While the biological limits of human lifespan remain finite, healthspan — the period of life spent in good health — can be significantly extended through conscious choices. Scientific evidence supports the view that lifestyle, psychosocial resilience, and contemplative practices can mitigate genetic vulnerabilities and enhance quality of life.

Rather than seeing death as solely inevitable, contemporary science encourages a shift toward agency in aging: choosing pathways that reduce suffering and foster vitality. Intergenerational love and responsibility remain crucial motivators for this pursuit, linking the biological reality of aging with the philosophical search for meaning.

References

- Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. Free Press.

- Chaix, R., Alvarez-López, M. J., Fagny, M., et al. (2017). Epigenetic clock analysis in long-term meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 85, 210–214.

- Doll, R., Peto, R., Boreham, J., & Sutherland, I. (2004). Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ, 328(7455), 1519.

- Epel, E. S., Puterman, E., Lin, J., et al. (2016). Meditation and telomere length: evidence from humans. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 119–128.

- Herskind, A. M., et al. (1996). The heritability of human longevity: a population-based study of 2872 Danish twin pairs born 1870–1900. Human Genetics, 97(3), 319–323.

- Horvath, S., & Raj, K. (2018). DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(6), 371–384.

- Kenyon, C. J. (2010). The genetics of ageing. Nature, 464(7288), 504–512.

- Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012, 278730.

- Longo, V. D., & Mattson, M. P. (2014). Fasting: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metabolism, 19(2), 181–192.

- López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194–1217.

- Orlich, M. J., et al. (2013). Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(13), 1230–1238.

- Patrick, H., & Nicklas, T. A. (2005). A review of family and social determinants of children’s eating patterns and diet quality. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 24(2), 83–92.

- Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 1–70.

- Rehm, J., Mathers, C., Popova, S., et al. (2009). Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use. The Lancet, 373(9682), 2223–2233.

- Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2019). Leading a meaningful life at older ages and its relationship with social engagement, prosperity, health, biology, and time use. PNAS, 116(4), 1207–1212.