Myopia, Perceptual Adaptation, and Psychological Correlates: A Scientific Overview

Abstract

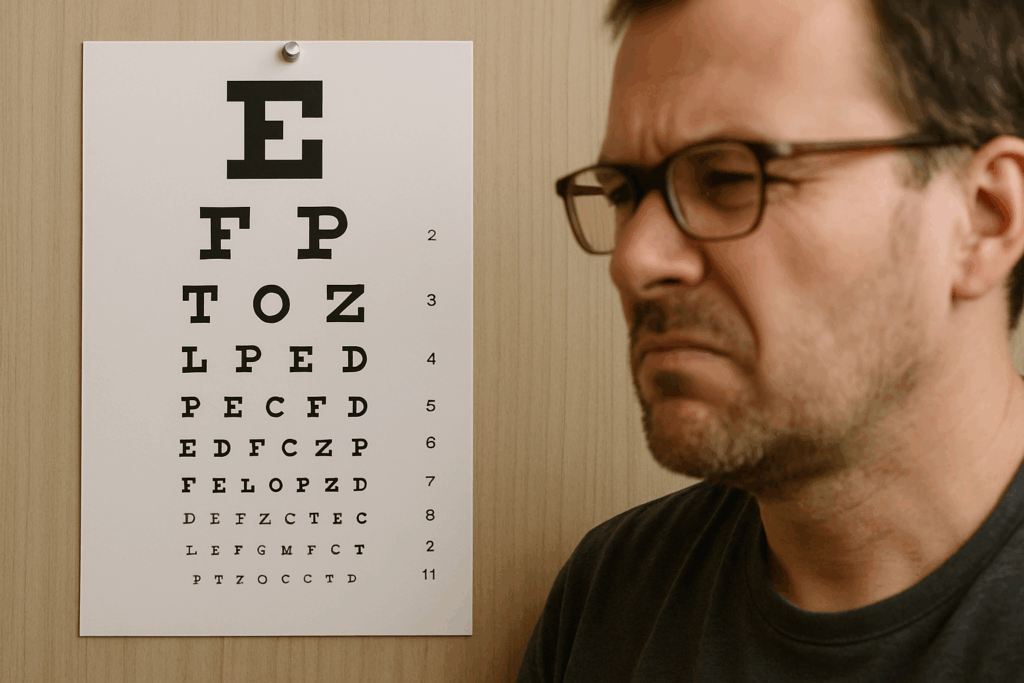

Myopia, or nearsightedness, is one of the most prevalent refractive errors worldwide, affecting nearly 30% of the global population and projected to reach 50% by 2050. While its biological mechanisms and optical corrections are well studied, less attention has been paid to its psychological and experiential implications. This article reviews the scientific literature on the relationship between visual impairment, perception of reality, and possible links with introversion, retrospection, and imaginative engagement.

1. Introduction

Myopia is characterized by elongation of the eyeball or refractive anomalies that cause light to focus in front of the retina, resulting in blurred distance vision. Beyond the clinical and epidemiological importance, myopia has psychosocial dimensions: how individuals adapt to blurred vision may influence personality development, self-perception, and modes of engagement with external versus internal reality.

2. Biological Basis of Myopia

The etiology of myopia is multifactorial. Genetic predisposition plays a substantial role, with twin studies estimating heritability between 60–80% (Hammond et al., 2001). Environmental factors such as reduced time spent outdoors and increased near-work activities (e.g., reading, screen use) significantly contribute to onset and progression (Holden et al., 2016; Morgan et al., 2012).

3. Psychological Consequences of Myopia

Several studies have explored whether refractive errors correlate with personality traits and psychological tendencies:

- Introversion and Social Withdrawal: Some evidence suggests individuals with uncorrected myopia may avoid group activities, particularly sports, due to functional disadvantage, potentially fostering introversion (Dirani et al., 2010).

- Academic Orientation: Myopic children often demonstrate higher academic achievement, possibly linked to increased near-work (Mutti et al., 2002). This has been described as a “myopia–intelligence” correlation, though causal pathways remain debated.

- Imaginative and Retrospective Engagement: Blurred distance vision may encourage inward focus, daydreaming, and reliance on mental imagery. While largely anecdotal, parallels can be drawn from research on sensory compensation, where reduced sensory clarity enhances imaginative processing (Miller & Saygin, 2013).

4. Perception of Reality and Visual Clarity

Vision is the dominant human sense, contributing over 70% of environmental sensory input. Altered visual input can reshape cognitive mapping of reality. Studies on perceptual psychology show that reduced clarity increases reliance on internal schemas and memory (Brady et al., 2011). This suggests myopia, particularly if uncorrected, could foster retrospective and introspective habits, influencing how reality is filtered and interpreted.

5. Adaptive Mechanisms and Identity

The decision to avoid corrective lenses for prolonged periods, as some individuals do, may create an identity shaped by “half-seeing.” This adaptation may foster resilience, heightened reliance on non-visual cues, or inward creative exploration. The metaphorical distinction between “physical short-sightedness” and “supernatural perception” resonates with cognitive theories of perception that emphasize multi-modal integration and the role of imagination in bridging sensory gaps (Clark, 2013).

6. Conclusion

Myopia is not only a clinical condition but also a perceptual and psychological state with potential influence on personality development, coping strategies, and creative worldviews. While the empirical link between myopia and traits such as introversion or imaginative richness requires further research, existing findings suggest that visual impairment shapes both external interactions and internal landscapes.

References

- Brady, T. F., Konkle, T., Alvarez, G. A., & Oliva, A. (2011). Visual long-term memory has a massive storage capacity for object details. PNAS, 105(38), 14325–14329.

- Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204.

- Dirani, M., et al. (2010). Refractive errors and personality in young adults. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 30(3), 300–306.

- Hammond, C. J., Snieder, H., Gilbert, C. E., & Spector, T. D. (2001). Genes and environment in refractive error: The twin eye study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 42(6), 1232–1236.

- Holden, B. A., et al. (2016). Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 to 2050. Ophthalmology, 123(5), 1036–1042.

- Miller, L. M., & Saygin, A. P. (2013). Individual differences in sensory and imaginative vividness. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 632.

- Morgan, I. G., Ohno-Matsui, K., & Saw, S. M. (2012). Myopia. The Lancet, 379(9827), 1739–1748.

- Mutti, D. O., Mitchell, G. L., Moeschberger, M. L., Jones, L. A., & Zadnik, K. (2002). Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children’s refractive error. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 43(12), 3633–3640.